Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge all the interviewees as well as staff at the Tour du Valat for their generosity with their time and insights. In addition I would like to thank the Tour du Valat for hosting me during my fieldwork, Prof.’s Nikoleta Jones and Nick Bernards for their feedback on this article, and the Mutations en Méditerranée editorial team, including comments from two anonymous referees, for their close editing and criticisms. Finally, I thank the Leverhulme Trust Doctoral Scholarships Programme which has funded this research.

Introduction

Mediterranean coastlines are often discussed as vulnerable to the effects of climate change (Cramer et al. 2018, Fader et al. 2020, Nicholls and Hoozemans 1996, Picon 2020). One such example is the Camargue delta in southern France, an area that falls between the Grand Rhône river to the east and the Petit Rhône to the west. Considered one of France’s most climate-vulnerable areas because of its low-lying terrain, susceptibility to coastal erosion, sea-level rise and increased salinisation of the soil (PECHAC, 2022), the Camargue is also home to high levels of biodiversity and ecosystems that have been relatively undisturbed compared to neighbouring industrial and touristic areas. Looking at the ways in which these ecosystems play a role in the delta’s susceptibility to climate change, this article interrogates the ‘vulnerability’ of one site in the Camargue by analysing the political ecology of a local ecosystem restoration project.

The ecology of the Camargue consists of wetlands, coastal ecosystems and saltmarshes. There is extensive agriculture in the north where swamps have been converted into pasture, and salt harvesting in the south (Picon 2020, Segura, Thibault and Poulin 2018). Rising sea levels have heightened tensions in a context with historically oppositional stances to ecosystems, characterised as “irreconcilable cultures” (Picon 2020, p. 2) between mastering ecosystems and adapting to them; between producers (economic actors) and protectors (environmentalists). These tensions have exposed an ambiguity about the ‘naturality’ of the Camargue: “With hundreds of kilometres of embankment, thousands of kilometres of canals, dozens of pumps, the delta is a system both natural and artificial [own emphasis], developed over the course of centuries, the product of ecological upheaval, and the co-evolution of the river [the Rhône], the sea and human development” (Mathevet 2004, p. 29). The use, flow and salinity of water have been central to its economic activity, influenced by technical constraints and by contestations between public and private actors (Allouche and Nicolas 2011, Picon 2020).

This case study follows one site of competing interests: the restoration of 8,500 ha of formerly exploited saltmarshes. The very features that made the site advantageous for salt extraction – proximity to the sea and flat landscapes – not only led to the development of industry and residential areas but also rendered it susceptible to potential flooding and submersion in the near future. Whereas the restoration project seeks to re-establish connections between the interior lagoons and the sea, thus allowing the erosion of seawalls, certain members of the local population and the salt company have questioned such a strategy, insisting instead on fortifying the sea protection infrastructure that remains. This article will show that one avenue to engage these contradictions is in the framing of the site’s management as a “nature-based solution”. Nature-based solutions (NbS) are commonly defined as “actions to protect, sustainably manage and restore natural or modified ecosystems, which address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, while simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits” (Cohen-Shacham et al. 2016). However, such an interpretation largely depends on whether landscapes formed by human activity – such as the saltpans in the Camargue – are understood as natural or not.

Political ecology is useful for analysing vulnerability because it explores both structural and site-specific factors: drawing from environmental sociology, environmental history, human geography, and anthropology, political ecology foregrounds political economy as the most fundamental determinant of ecological degradation (Robbins 2012). Conversely, it centres ecological outcomes in its analysis of the political economy.

This article first discusses the concept of vulnerability and where political ecology scholarship can bring analytical focus to established definitions of vulnerability. It then explains the research methods and a background to the case study site. I discuss different components of vulnerability, and argue why the discursive and material implications of ‘nature’ in this regard are important. I further discuss the framing of the site’s management as a ‘nature-based solution’, a phenomenon that has mostly been treated in urban settings (Johnson et al. 2022). As this case study shows, the application and perception of this concept are mixed.

Vulnerability as a lens to socio-environmental tensions

The ways in which vulnerability is understood shed light on how different forces impact social actors over time, but also how these actors can respond (Adger 2006). While Wisner et al. (2003, p. 11) define vulnerability as the “capacity to anticipate, respond to and recover from a hazard”, Adger (2006, p. 268) describes it as a condition rather than a type of responsiveness: “Vulnerability is the state of susceptibility to harm from exposure to stresses associated with environmental and social change and from the absence of capacity to adapt.” In both definitions, vulnerability can be determined by future damage that may be incurred from one-off or continual events. Recovering from damage to oneself, one’s livelihood, or one’s assets is more challenging the more vulnerable someone or a group is (Wisner et al. 2003). Where vulnerability is concerned with processes or material objects considered as ‘natural’, however, raises questions about what constitutes nature.

Much vulnerability research has been developed in human ecology, hazards research, resource management or livelihood research (Adger 2006, Eakin and Luers 2006, Bankoff et al. 2004, Cutter 2003). Although not always explicitly described as such, vulnerability has been a concern in much political ecology scholarship (Bolin and Stanford 2005, Collins 2008, Hewitt 2019). Robbins’ (2012, p. 20) description of political ecology approaches involves “a certain kind of text to address the condition and change of social/environmental systems, with explicit consideration of relations of power”. That approach aligns with Eakin and Luers’ (2006) assessment of where political ecology has contributed to debates around vulnerability: instead of establishing a definition or conceptual tool for vulnerability, political ecology has highlighted the historical and political aspects which differentiate experiences of vulnerability. This is not to say that the focus on vulnerability from other fields necessarily reflects apolitical ecologies. Wisner et al.’s and Adger’s definitions can still be compatible with a political ecology perspective, precisely by accommodating the political economy context:

“Vulnerability to environmental change does not exist in isolation from the wider political economy of resource use. Vulnerability is driven by inadvertent or deliberate human action that reinforces self-interest and the distribution of power in addition to interacting with physical and ecological systems” (Adger 2006, p. 270).

Watts and Bohle’s (1993) development of the concept of vulnerability is a good example of maintaining sensibilities consistent with political ecology. Their threefold analysis of the “space of vulnerability” consists of entitlement (the command over resources), empowerment/enfranchisement (relations between the state and civil society), and political economy (structural and historical determinants of class relations). Their framing of vulnerability integrates conceptual tools assessing ecosystems and resources, with tools that help understand processes of capital accumulation and contradictions in the economic system.

In addition, given the range of actors involved in the restoration project analysed in this article, political ecology’s ability to integrate and draw links between variables at different but nested scales (Robbins 2012) lends granularity and analytical strength. Importantly, political ecology has engaged with questions around naturality and artificiality, critically analysing mainstream understandings of nature.

This research will add to existing political ecology approaches applied to studies on the Camargue. Mathevet et al.’s (2015) work on reedbed conservation on the Scamandre marshes, a smaller natural reserve in the broader Camargue to the west of the Petit Rhône, utilises an historical perspective to analyse changes in water regimes and the political economy of land investment. In their study, they outline cyclical trends in the competition of actors, incompatible interests regarding spaces and water, and resultant conflicts of control over water levels and salt levels. This article shows that similar trends revolve around competing interests in an otherwise quite different part of the Camargue. There are certain advantages with respect to understanding vulnerability when contextualising the historical development of the former saltworks. The risk to people and assets from rising sea levels results from the creation of a site where the extraction of salt and need for labour drove the establishment of industry and a village in an isolated, exposed part of the Camargue.

Research methods

The research was carried out as part of a study on the social impact of projects described as ‘nature-based solutions’. Fieldwork involved semi-structured interviews with 27 actors familiar with the site and/or directly involved in its management, of which seven addressed aspects of vulnerability (see the list before the bibliography). I was predominantly speaking with, and working alongside but independent to, staff of the Tour du Valat, a research station focused on the conservation of wetlands in the Mediterranean. The Tour du Valat is a private scientific foundation which is also recognised as public interest, and it is one of the co-managers of the restoration site. The staff members at the research station were mid- to senior-level, and engaged to different degrees in research, project implementation and managerial roles. Other interviewees external to the Tour du Valat consisted of individuals with in-depth knowledge of and experience with either the restoration project, or the sites in and around where the project has been implemented. These include a resident of Salin-de-Giraud and former employee of the saltworks (who had worked on its hydrological dynamics); two residents of Salin-de-Giraud and members of a local association established to mediate engagement with different stakeholders; and a tour operator, living in the same locality, who has led tours on the site.

Interviewees were identified through two approaches: firstly, by consulting the Tour du Valat’s lead for the restoration site, which was the most immediate means of getting access considering that I had no prior connections; and secondly, with snowball sampling which broadened the profile of interviewees, particularly beyond those working for or with the research station. The transcribed interviews were analysed through thematic analysis. These insights were then complemented by locally published or historical non-academic literature specifically on the southeast of the Camargue, and grey literature (see list at the end of this article).

The restoration site

Despite salt production and environmental conservation being strongly identified with the Camargue, both industrial and environmentalist aspects are relatively recent phenomena of the modern period. A review of the historical background of the site is useful to contextualise the politics of its use over time by a variety of different actors.

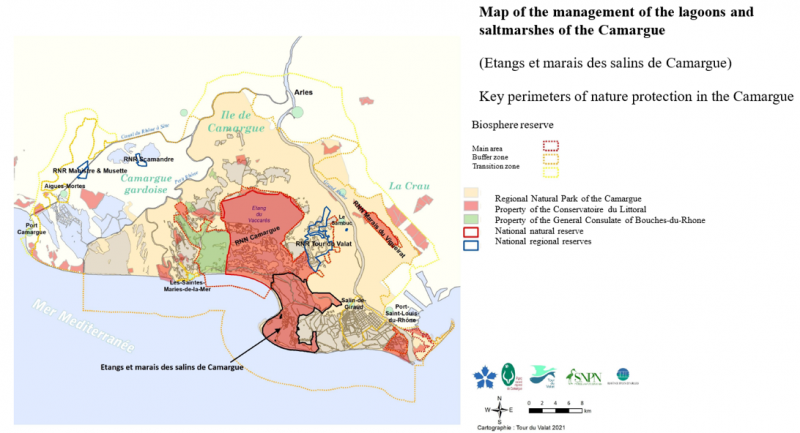

The saltworks studied in this article are located in the southeast of the Camargue delta (see map in Figure 1), a section which had been economically marginalised before industrialisation compared to the agricultural north (Picon 2020). The area in question is an expanse of saltmarshes, ponds and wetlands on the coastline, bordered by industrial salt harvesting to the east, agriculture to the north, and a national natural reserve to the west. This area has been labelled as the ‘Étangs et marais des salins de Camargue’ (Camargue lagoons and saltmarshes), or EMSC, as in the map below.

Map of the Camargue delta (Parc naturel régional de Camargue et al.,2022)

Map production: Loïc Willm, Emilie Luna-Laurent (Tour du Valat), Marie-Lou Degez (Parc de Camargue). Publication: Parc naturel régional de Camargue et al. (2022). Translated to English by the author.

Prior to monopolistic industrial salt extraction, and interest from researchers, environmental actors and the tourism sector, the area was used for small-scale hunting, fishing, and pasture. The beginning of the salt industry in the mid-1800s led to a direct impact on the landscape: the industry established protective dykes, pumps and groynes, a form of infrastructure that limits erosion. The salt company at the time (now known as the Salins du Midi) thus controlled the connection between lagoons and the sea to retain high levels of salinity (Picon 2020). The company attempted to reduce the vulnerability of its production to hydrological or meteorological fluctuations through its privately operated interventions in water levels (Segura, Thibault and Poulin 2018). Private control of water levels had also been experienced in the Scamandre marshes mentioned earlier (Mathevet et al. 2015).

By the 1960s, the marshes in the EMSC comprised one of Europe’s largest saltworks, with 13,000 ha of exploited saltpans (Picon 2020). The Salins du Midi salt company had been a key supplier to a local chemicals manufacturer, which in the 1990s and 2000s changed ownership and reduced its purchase of salt (Roché and Aubry 2009). Similarly, the salt company itself faced several acquisitions between 1997 and 2004 as ownership shifted from industrial managers to financial investors. After these waves of mergers and acquisitions, the company shrunk production by 60% in 2007, and reduced its workforce by 50% to finance debts resulting from the acquisitions (Béchet et al. 2011, Roché and Aubry 2009). The 2008 financial crisis exacerbated these difficulties; eventually, the Salins du Midi listed 9,000 ha of saltpans for sale.

These parcels were bought by a public establishment, the Conservatoire du littoral, and demarcated for an ecological restoration project. Created in 1975, the Conservatoire’s mandate is to protect France’s coastline (Allouche and Nicolas 2015). More recently, it has had to integrate the risks of marine submersion and coastal erosion into its coastal zone management to face the rise of sea level (Allouche and Nicolas 2015). Indeed, the Camargue’s coastline is consistently shaped by a combination of ocean currents, storm intensity, coastal dunes, and the condition of seawalls and groynes. Currently, the protective shoreline dykes around the former saltworks are not being maintained, in order to allow for ecosystem restoration. This has raised a contention with the saltworks still in operation, that is fairly common in other parts of the Camargue, around the upkeep of infrastructure on land that is publicly owned. It is also at odds with unwavering confidence in hard infrastructure’s ability to perpetually master hydrological processes and provide safety. This agency over landscapes and waterscapes was a key part of establishing the salt industry and the adjoining village, which both find themselves more vulnerable to physical threats.

Following the sale of the former saltworks, the co-management of the site was designated to the regional natural park of the Camargue, the Tour du Valat, and the National Society for the Protection of Nature (SNPN). The regional park is officially tasked with supervising the sustainable development and protection of the natural and cultural heritage of the delta, and already oversees much of its surface area (see Figure 1). It does not have regulatory power; however, it is responsible for facilitating consultation with local actors.

This historical overview thus shows a variety of actors and spaces operating in the Camargue delta over the modern period. Inheriting the industrial development of saltmarshes in the 19th century and the arrival of environmental actors in the 20th century, the delta has seen its coastline change from the various initiatives of these actors. A study of the multiple statuses of ‘nature’ protection in the Camargue should therefore engage with several actors, from public institutions, research centres, private companies to local inhabitants, as well as its different spaces, including the former saltworks.

Different understandings of vulnerability

Throughout the histories of governance and vulnerability in the EMSC, tensions have arisen between competing understandings of nature as something either external to or including human activities. Some of these tensions play out in the Camargue generally, but it is the unique traits of the saltworks which shape its distinct vulnerability and status as a natural space. More specifically, these tensions have crystallised around the renaturation project in question.

Vulnerability of biodiversity, assets and coastlines

The vulnerability of the former saltworks is understood differently in institutional literature, depending on whether it is defined by co-managers, public institutions or researchers. The restoration site management plan mostly discusses environmental vulnerability experienced by particular species, rather than the coastline itself as susceptible to sea-level rise or dynamic salinity levels. In that case, the main threat is the degradation of the site, for instance through vehicle circulation. Restoring the site’s original hydrological dynamics allowed for an increase in biodiversity, including fish and certain waterbirds1, revealing that their survival had been more vulnerable in the areas of salt extraction with controlled salinity and water levels.

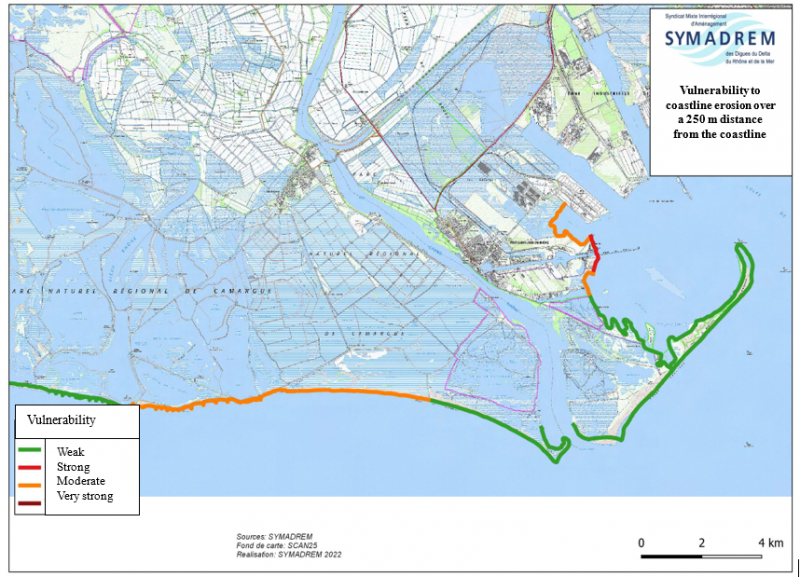

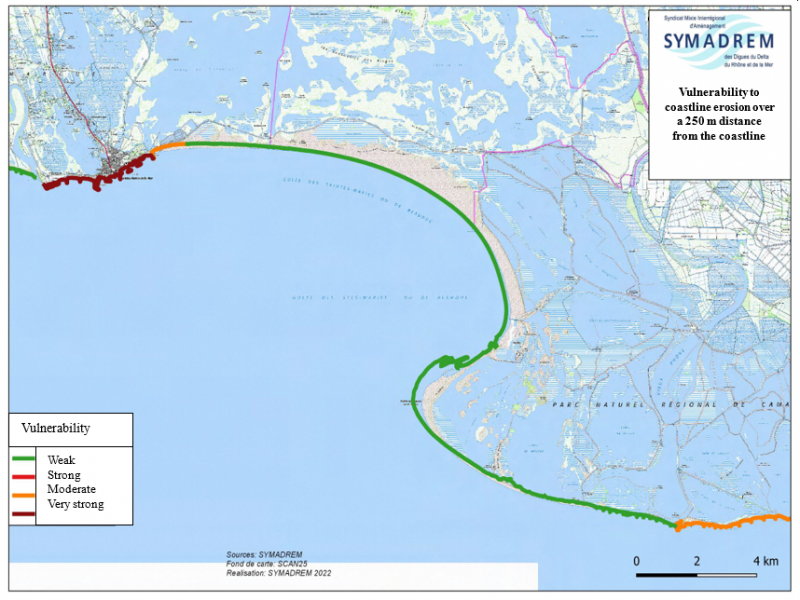

The Syndicat mixte interrégional d’aménagement des digues du delta du Rhône et de la mer (SYMADREM) is a local public body in charge of constructing protective infrastructure from both the Mediterranean sea and the Rhône river. It is also responsible for the local implementation of aquatic and flood-prevention-related laws2. The SYMADREM syndicate is thus concerned with coastline vulnerability, which it assesses as a function of the risk of shoreline erosion (SYMADREM 2022). The organisation includes the following parameters in defining this vulnerability: the rate of coastal retreat, the presence of existing infrastructure, and changes in sediment (SYMADREM 2022, p. 276). It then classifies vulnerability as low, moderate, strong or very strong. Further categories were established for vulnerable areas, indicating if they were: natural spaces (considered the least vulnerable), mixed spaces with some degree of buildings or infrastructure, or urbanised spaces where relocating existing buildings is very difficult (generally considered the most vulnerable). Along the coastline bordering the EMSC (see Figure 2), the vulnerability was considered weak to moderate (SYMADREM 2022). Here, vulnerability is conceptualised at a landscape scale, encompassing the physical features of the coastline as well as living and non-living entities inland. SYMADREM’s framing of vulnerability is therefore contingent on where it identifies natural spaces, which it regards as areas without human presence, infrastructure or assets. The more ‘natural’ space there is, the less vulnerable the area.

Map detailing SYMADREM’s vulnerability classification along the former and current saltworks (SYMADREM 2022)

Sources: SYMADREM; Base map : SCAN25; map production: SYMADREM. Publication: SYMADREM (2022). Translated to English by the author.

While SYMADREM defined natural areas as those empty of any human activity, and thus not very vulnerable, the PECHAC, a research project addressing climate change and socio-ecological impacts in the Camargue, framed nature and vulnerability slightly differently. Its suggested route to address the risk of hazards is to “allow natural processes to take their course so that natural environments can establish themselves and act as local buffers in coastal erosion dynamics” (PECHAC 2020, p. 19). However, the same report advises doing so “when there are no, or no more, economic issues at stake and provided that people’s safety is ensured” (PECHAC 2020, p. 19). In other words, the PECHAC situates nature itself as a means to reduce the vulnerability of spaces, but only when that vulnerability does not extend to human or economic activities. The tension here lies in deciding how much ‘naturality’ to integrate into adaptation approaches which implicate human economic activities such as salt production – which are of concern to the Salin-de-Giraud residents. Therefore, when applied to the EMSC, this broader approach incorporates concerns from actors who argue that allowing natural processes into adaptation strategy does in fact threaten human safety and economic issues.

The diverse readings of vulnerability show that, depending on the actor, and despite a common acknowledgement of coastal retreat, framings of vulnerability and suggested responses vary. A potential source of these tensions are the values that different actors associate with the land in question, and the personal and economic interest in how it is shaped (or not) by continued human intervention. Although focused on the risk of physical hazards, such tensions can also be traced to the specific geographic and social features of the area.

Social vulnerability

The village of Salin-de-Giraud and the adjacent salt production are situated on the periphery of the Camargue. The effect of spatial remoteness is acutely felt by villagers, and adds to its characterisation as an “enclave” (Guyonnet 2024, p. 9). The salt industry, which in the early 20th century had recruited its workforce from outside of the Camargue, nevertheless provided means for leisure and social services in this remote location, such as housing, a school, a doctor and public spaces to socialise – a system characterised as paternalist (Roché and Aubry 2009). However, the downscaling of salt extraction led to a loss of employment for the successive generations who remained in the village, and an end to the related social benefits and livelihood security that had been guaranteed for their predecessors. The dynamic pressures of globalised markets and financialisation that resulted in the restructuring and downsizing of the salt company thus had very local consequences. Nevertheless, confidence in the salt company and an appreciation for the current owner persist within Salin-de-Giraud, as expressed by a former employee (Interviewee 7):

“The saltworks are going well. [The company] has just signed a new contract with the factory on the other side of the Rhône. And he [the owner] has invested in tourism and all that. It’s good because if not there would be nothing left at Salin-de-Giraud. So it’s gone well, and what’s more, I hear that he genuinely likes Salin-de-Giraud. Which is all the better for the residents and especially those who still work at the saltworks.”

This testimony indicates that the economic activity of salt production is still a central part of life and identity in Salin-de-Giraud, and its prospects and security are still seen as intimately tied to the prospects of the village itself.

Perceived vulnerability leveraged to oppose restoration

In 2024, the Salins du Midi salt company launched a ‘Manifesto for a Living Camargue’, which motions to safeguard “jobs, wealth and nature” (Groupe Salins 2024, para. 10). The manifesto explicitly rejected “renaturation” as a solution to the vulnerability of livelihoods and territory.

To understand this manifesto, it is worth revisiting the events that took place since the designation of the EMSC as a site for ecological restoration. Immediately following the final land sale in 2012 and the start of the restoration work, a succession of heavy storms struck the coastline, badly damaging the existing seawalls. This forced the Conservatoire du littoral and the co-managers to consider reinvesting in the damaged seawalls to buffer potential storms that would come after, before a public consultation on the matter could be held. In line with the Conservatoire’s position of prioritising the protection of coastal ecosystems rather than infrastructure, the seawalls were not repaired. According to one of the co-managers (Interviewee 1), this decision was perceived quite negatively by certain inhabitants, and led to a feeling that their agency in the restoration project was undermined.

Other events fuelled this friction. The flamingos that had nested on an artificial island in the EMSC migrated west to another saltpan soon after the Conservatoire bought the Fangassier lagoon, where the island had been. This prompted some actors (the salt industry, local residents) to consider its new owner, the Conservatoire, and the new co-managers as incompetent, and resulted in discontent among elected officials who had promoted the area to tourists wanting to see the emblematic bird of the Camargue (Mathevet and Béchet 2020).

Additionally, the co-managers of the site found themselves needing to work in areas where local groups had had certain use rights previously. These privileges, before the land sale, had been administered by the salt company within its paternalist approach: rights to hunting, fishing and harvesting within the area were reserved for employees of the saltworks and their families (Interviewee 4). Following the sale to the Conservatoire, regulations around access made the site simultaneously accessible to a wider public, and subject to management styles with ecosystem restoration (rather than salt extraction) in mind. Such management styles disrupted the previously felt entitlement to exclusive use of the site.

It is with these sentiments of urgency and protection that the “Manifesto for a living Camargue” may resonate. Its messaging appealed to a sense of protection from local inhabitants’ agency in determining their future livelihoods and properties, which are considered at risk from sea-level rise or the restoration project, or both. At the same time, the manifesto omitted any reference to vulnerability to financial conditions affecting a singular dominant actor, the salt company, an economic feature which historically shaped socio-economic vulnerability.

The manifesto states: “Salt remains a rich resource and an asset for the Camargue. The forces threatening it can easily be contained and regulated if we so wish. For the economy, jobs, landscapes, birds and biodiversity. For everyone, in fact.” (Groupe Salins 2024) What the manifesto leveraged were the values residents hold in terms of being able to access and live in spaces to which they hold a strong attachment. It spoke to the vulnerability people experienced from climate change in “not only their objective, exterior world, but also their subjective, interior world” (O’Brien and Wolf 2010). In this narrative, the protection of salt production represents the protection of the Camargue, whereas ecosystem restoration represents a declinist ideology. Reinforcing built infrastructure represents proactively responding to the Camargue’s immediate threats and local empowerment, whereas renaturation represents abandonment. Decisions are seen to be made by actors (the Conservatoire du littoral, the site co-managers), away from the traditional inhabitants of the area in Salin-de-Giraud and therefore less qualified. Such visions of the management of the site contributed to tensions between a company campaigning for the reemergence of industrial growth, and efforts to re-establish ecological functioning – which are synthesised in the following description: “The salt producer invokes economic reversibility while the naturalist defends ecological reversibility” (Roché and Aubry 2009, p. 144).

For several residents, given that the present form of the Camargue resulted from human intervention, whether in the form of seawalls or dykes along the Rhône, to claim a return to ‘nature’ was misguided. According to the manifesto, the landscapes that are rich in productivity and biodiversity but under threat from sea-level rise are the product of years of tireless human intervention (Groupe Salins 2024). A more cautious view was expressed by one of the former salt workers (Interview 7), however, less convinced of a purely human-shaped surrounding. When discussing the infrastructure required to address sea level rise, he suggested: “It’s difficult, because one can’t do much in the face of nature. The company has done well though, by building jetties, and protecting everything. But it is all against nature… And the sea has incredible power.” The various suggestions on how to address vulnerability (and what the sources of vulnerability are) show that nature is far from being understood uniformly.

Natural solutions to vulnerability, and vulnerability to nature

Integral to these competing understandings of vulnerability surrounding the former saltworks is the conception of nature. An important historical representation of nature in the Camargue is captured by the European Union biodiversity conservation policy Natura 2000. Under two directives, France, with other European states, was obliged to designate a network of sites for the protection of ‘nature’. Immediately, a top-down prescription that specified what nature should look like was implemented in the Camargue, with the entire region having been chosen as a Natura 2000 area (Picon, 2020). Natura 2000 also introduced European-level priorities into the Conservatoire du littoral’s coastal protection strategy.

In the 1980s and 1990s, environmental organisations started embracing notions of “integrated conservation” and several concepts which fell alongside or under such a philosophy: sustainable development, community-based management or socio-ecosystem adaptive management (Therville et al. 2012). They were adopted by the French state to a certain degree, in particular regarding biodiversity conservation (Claeys-Mekdade 2003, Therville et al. 2012). This was partially achieved through Natura 2000. Whilst the management of some locations integrated local consultation, for others it did not feature at all. In those cases, it instilled a perception that Natura 2000 was a political project ringfencing outdoor spaces. According to one of the staff in the Tour du Valat research station, the EU plan was perceived by residents as a way to “put nature in a glass casing” (“mettre la nature sous cloche”, Interviewee 5); to be viewed but not touched, and accessed only by a few. This notion of overly protecting spaces has been questioned (see Cosson et al. 2017), as well as refuted as hyperbolic and indicative of “anti-conservationism” (Grenier 2015, p. 68). In either regard, “mettre la nature sous cloche” is a phrase that has reflected a politics wary of conservation efforts, particularly exacerbated in the Camargue where landscapes have been shaped by human activity for centuries. There is a marked difference in tolerance towards land access changes for conservation reasons, compared to access changes for farming or industry.

Positing nature as a solution

A new concept aiming at expanding the scope of conservation efforts towards social priorities is called ‘nature-based solutions’. It is important to recognise that when the project was initially implemented, it was not conceived of as an NbS. It was only later that actors involved in the co-management started referring to it as an NbS, despite practices remaining the same (Interviewee 1). NbS exemplifies a popular trend in international advocacy to portray nature as a buffer against a myriad of issues. The concept was introduced in 2008, and in 2020, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) released a ‘Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions’, explaining that to qualify as an NbS, an intervention must “have significant and demonstrable impacts on society” (Andrade et al. 2020, p. 6). As the IUCN is a key global institution for biodiversity policymaking, this definition is widely used.

An important tension predating NbS is whether people are considered part of ‘nature’. The tension is perhaps particularly elevated in the Camargue because the extent of human presence – that is, social structures, infrastructure, and economic activities – has been instrumental in developing spaces that may be viewed to different degrees as ‘natural’. Such a hybridity leads to a range of understandings, at times portraying nature as a product of, subject to, or proscription against human activity. It is notable that within the Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions, there is no definition of what is meant by nature. Similarly, the ‘society’ associated with ‘societal challenges’ is not defined. Which parts of society are meant? How far does society extend beyond the immediate surroundings of the project at hand?

One vision of a more ‘natural system’ which the restoration site raises is to re-establish a hydrological regime which is found along Mediterranean coastlines with less human intervention. It is precisely by not reconstructing the damaged seawalls that nature can take its course. With sea-level rise, this vision of a natural flow of water raises alarms for the salt industry, which perceives a risk to its production, as described by a local resident (Interviewee 6):

“In the site of current extraction, it (sea surge) happened once last year; and I think the Salins du Midi worry that one day the water level will rise higher than normal, and the seawalls between the company’s land and the former saltworks will break. And at that point, the production materials of the Salins du Midi will be damaged… I’ve already seen (in 2005) a sea incursion which overwhelmed the Salins du Midi when there was a huge storm”.

The salt company cannot financially commit to investing in infrastructure that does not directly sit on its property, even though it sees the degradation of this infrastructure as a threat to its production and revenue.

Property, competing knowledge, and implementation

The transfer of land from the Salins du Midi to the Conservatoire had important consequences in terms of the balance of power regarding water and land management in the Camargue (Mathevet and Béchet 2020). As Mathevet et al. (2015) argued in the study on the Scamandre marshes, such power transfers also highlight a dynamic cycle of water management regimes characterised by periods of disruption and stability. That the Conservatoire du littoral was now an owner of a significant amount of land in the Camargue may have been perceived as a threat to certain actors, given its objectives set by Natura 2000 and other protection strategies. It implied that state-level decisions would be effected in spaces that previously had been produced and determined based on the decision-making of local actors.

Where nature-based solutions, or allowing for natural hydrological and sediment patterns, can be particularly effective is in establishing long-term buffers against erosion at a low cost (Segura, Thibault and Poulin 2018). My discussion with one of the co-managers of the site (Interviewee 3) covered the fact that in the national context of budgetary austerity (see Cosnard 2024, Grandclement et al. 2022), low-cost spending on coastal infrastructure is more likely to receive national support, particularly for sparsely populated areas with reduced industrial activity. Nevertheless, by introducing processes of renaturation into the EMSC, the Conservatoire du littoral allowed for legitimate concerns about marine submersion to grow among residents (Interviewee 3). On top of fears around the erosion of seawalls and insecurities about the possibility of keeping coastal incursion at bay was the symbolic feeling of seeing land used for hunting or fishing being rendered less exclusive to locals, or governed by norms based on ecological priorities.

Caught among these economic interests, the presence of flamingos was a particularly sensitive topic. As a flagship species for the Camargue and its wetlands and a source of inspiration for tourism, flamingos became the “scapegoat of a still-awaited economic revitalisation, postponed as much as it had been promised, of Salin-de-Giraud” (Mathevet and Béchet 2020). Conservation ecologists tended to celebrate the reintroduction of constantly fluctuating ecological conditions such as salinity and water levels, characteristic of coastal and estuary ecosystems. However, because the breeding colony in Fangassier could no longer be carefully managed, the flamingos’ undisturbed reproduction could not be guaranteed. Thus, in the different approaches to vulnerability, some incoherence is notable regarding the acceptance of ‘unstable’ conditions. Whilst some promote embracing the instability of ecosystems, others champion taking action to eliminate as far as possible such uncertainty.

The politics of the manifesto appealed to the deep connection of local inhabitants to the territory, its ‘nature’, and their confidence in their own understanding of such ‘nature’. The manifesto portrays local residents and economic actors as equipped with a thorough knowledge of how to safeguard biodiversity, which they may consider superior to that of other groups without their specific experience. I would often encounter scepticism around the restoration project, captured by the following reflection on whether nature could act as a solution for Salin-de-Giraud: “We who are [actually] in Salin-De-Giraud, we see what’s going on… I don’t see how we can protect biodiversity if we let the sea enter” (Interviewee 3). The biodiversity in question is therefore the specific combination of species that has been allowed to develop during salt production.

The tension between conceptions of nature was not new for many residents. A local tour operator expressed a nuanced perspective on how nature is understood:

“It’s true that when we were living in Salin-de-Giraud until the 1990s, so before the Conservatoire du littoral bought the land, nature for us was everything that was around us. But it was a nature constrained by humans, because the Salins du Midi practically extracted the entire surface to the south. And there was nothing natural in fact. It was nature, but it wasn’t natural because there were dykes that obstructed the sea from entering, and at all times, the levels of water were managed by humans.”

It is apparent that for certain individuals who knew the site, ‘nature’ can very plausibly be an area in which non-‘natural’ processes or human activities occur.

Returning to the messaging of the site as a nature-based solution, there is in fact a specified combination of abandoning certain infrastructure whilst reinforcing or constructing others, in particular an inland dyke (Interviewee 2, Segura, Thibault and Poulin 2018). In fact, traditional construction was an integral part of re-establishing the ‘naturality’ of the restoration project: channels and openings between ponds were still necessary to allow for a reconnection between interior lagoons and the sea, which had previously been blocked from one another. However, this nuance seems to be lost under the label of ‘nature-based solutions’, and is certainly not acknowledged in the messaging of the manifesto. Furthermore, even though a full communications and consultation plan for the restoration project has been developed, it has yet to be implemented. Perhaps as a result, one resident of Salin-de-Giraud (Interviewee 3) expressed that certain local groups feel that the only priority of the management plan is towards an NbS. In this instance, they interpret such solutions as only based on the nature represented by sea-level rise, coastal retreat and complete lack of human intervention; unlike other understandings of nature which accommodate human infrastructure.

If there is commonality to be found between different responses of interviewees I spoke to, it was that for the time being, both ‘natural’ and traditional infrastructure have a role to play in rendering the Camargue coastline more resilient.

Implications and conclusion

This article has discussed the vulnerabilities of the former saltworks in the Camargue, brought into relief by the implementation of an ecosystem restoration project. Focusing on the hazards associated with sea-level rise, it showed how other factors relating to the spatial, social and political characteristics of Salin-de-Giraud and the EMSC influenced how different actors anticipated and responded to such hazards. Specifically, geographic isolation, marine submersion, and deindustrialisation were contextual factors influencing different understandings of vulnerability. Responses included calling for a revitalisation of industrial activity and even further human intervention in shaping the landscape on the one hand, and reintroducing hydrological flows and biodiversity on the other.

The tension is thus whether to operationalise nature, as a threat or as a “solution”, when discussing vulnerability, neither of which are fully covered by the definition of NbS. At an institutional level, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s definition of NbS identifies seven societal challenges. Two of these challenges, climate change and disaster risk, mention but do not define vulnerability, perhaps because of its complex relationship to nature. Without explicit reference to socio-economic and/or temporal dimensions of vulnerability, the IUCN’s framing of NbS is primarily concerned with physical rather than social components of vulnerability. Applying an exclusively NbS framing to interventions in the landscapes around Salin-de-Giraud might limit the ability to incorporate how the management of water dynamics, salt extraction, the related chemicals industry and the development of the village have all been the products of social relations. As such, vulnerability to sea-level rise is bound to the social structures supporting the industry and village. The degree to which nature is simultaneously perceived as universal or external to people makes it difficult to evaluate vulnerability via risks in society or nature (as per Wisner et al.’s definition), or of social-ecological systems (as per Adger’s framing), as both imply parsing out social vulnerability from ecological or ‘natural’ vulnerability.

The discrepancies between how nature is understood, communicated, and positioned in relation to human activity make discussions on vulnerability complex, as these discrepancies influence the understanding of exactly what is at stake and what is (or should be) within the influence of human agency. More broadly, the article has shown that such a qualitative and historical approach is useful for understanding vulnerabilities as a plurality.